The production of The Best Ancestral Mezcal, from a cultural perspective, is a pre-Hispanic legacy, as interpreted by Dr. Serrapuche. We believe our ancestors left us more than just the crafting of clay pots for distillation.

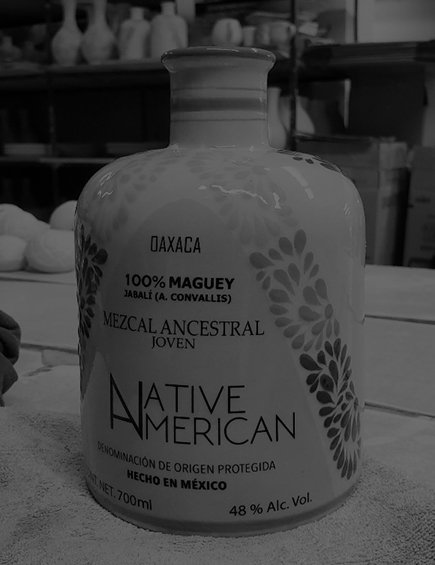

Our bottle was designed by BRS BlessedRemedySpirits.com

to convey the craftsmanship of Mexican hands, respecting the ancestral processes we have inherited. The cork reminds you where mezcal comes

from—a harvested agave piña rich in sugars.

For Oaxacans, the Tiliche represents a new figure in the Guelaguetza, the greatest festival of Oaxaca. It has become so beloved by locals that we all feel like tiliches. The wind music accompanying the tiliches' dance is joyful and festive, which is why we highlight the movement of their tattered cloths, their masks representing animals from the Putla region of Oaxaca, and the sharing of our traditions and customs.

“Putla de Guerrero, Oax.—In the early 1920s, a group known as the ‘Marmanos’ (now called ‘Viejos’) emerged. At first, they imitated the speech of elders, saying ‘Marmano’ instead of ‘Mi hermano’ (my brother). They often exchanged affectionate hugs.

Their outfits were covered in patches and strips, imitating torn clothing, as they proudly ‘showed off’ new fabric patches. Over time, the costume evolved from patches to tattered strips. This group became the most cherished and symbolic tradition in our town. Its founders were two elders from Putla: Don Heziquio Pimentel Terrones and Don Julián Terrones.

Initially, the ‘Marmanos’ danced without the little bull (torito). Later, they began bringing it out only during the last three days of Carnival.

They would hide the bull in different places—like grazing pens on the outskirts of town—and the next day, amid shouts and excitement, they’d gather ropes, palm cords, and lassos, along with palm baskets and trays of salt, inviting everyone to help find it. When they located the bull, they’d wrap vines, grass, or herbs around its horns, while others called out, herded, or lassoed it—all accompanied by lively wind music playing Carnival tunes.

Don Miguel Terrones recalled that in the 1930s, the patches were replaced with tiliches made from old, unusable clothing. Some wore hats made of old mats, while the masks remained crafted from small animal hides—opossums, raccoons, foxes, rabbits, squirrels, goats, and others. They added long cloth noses, stuffed with sawdust or fabric scraps, resembling two sausages in size. The disguised participants were treated to masa and goat barbacoa during meals.”